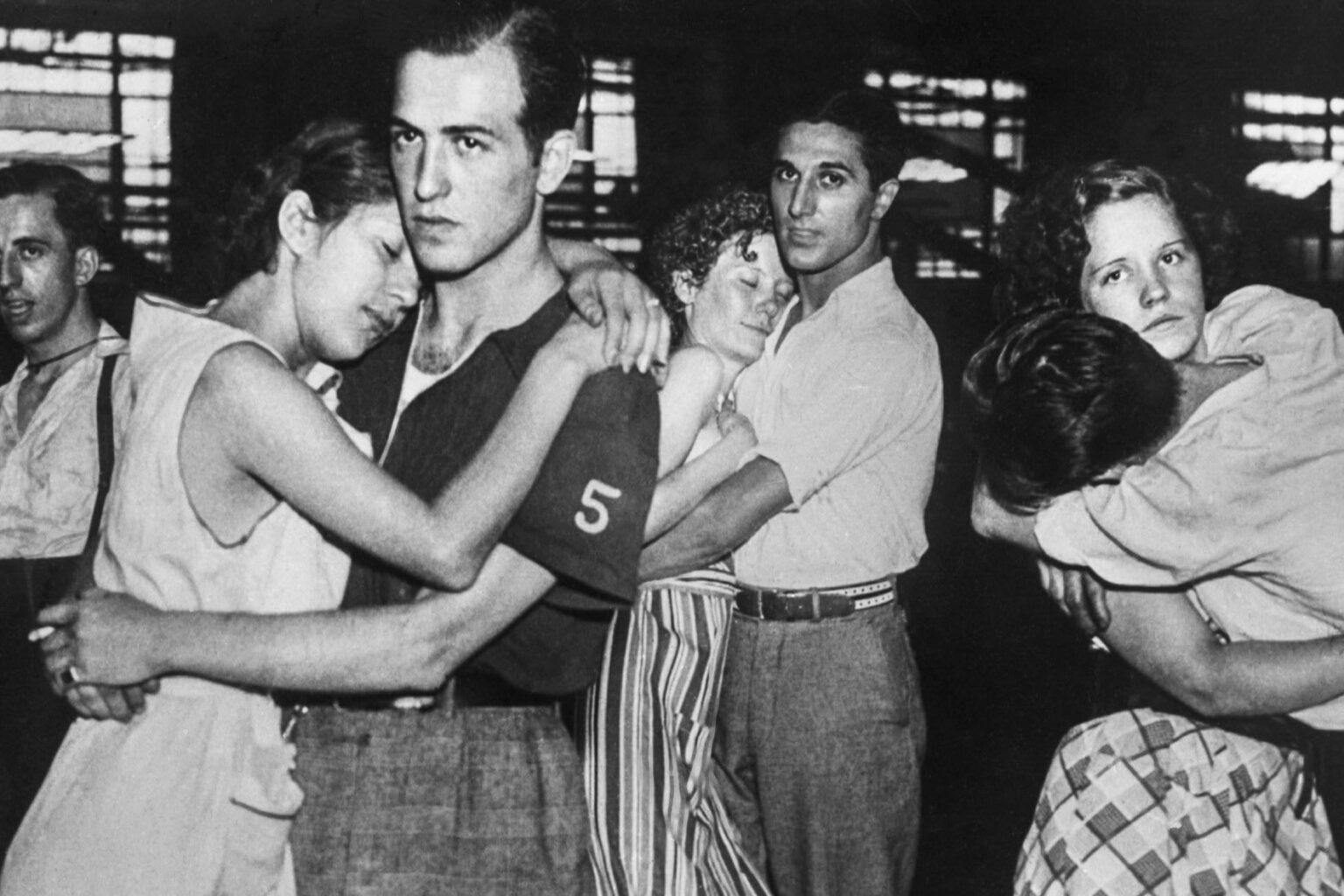

In the 1920s and 1930s, dance marathons captured the public’s imagination as a form of entertainment that promised not only fame but financial reward. Couples would stand on their feet, moving rhythmically for hours and, at times, days, testing not only their physical endurance but also their mental fortitude. While the kaleidoscope of lights painted an image of glamour and excitement, there lay beneath a grittier reality that many of the participants, especially those who have come forward years later, can attest to—a complex interplay of resilience and vulnerability that endurance athletes know all too well.

Dorothy Jenkins, now 92, emerged from those marathons, filled with a mix of nostalgia and caution. As a young woman, she envisioned an exhilarating dance experience that might even be financially rewarding. Yet, the reality of nearly ninety hours on the floor shattered her youthful illusions. Constant movement transformed into relentless exhaustion, where fatigue lingered heavily in her bones and her feet became painfully tender. In the world of endurance sports, this scenario mirrors the grueling hours athletes log in training sessions, where the line between perseverance and overexertion can be thin.

Jenkins and her partner faced a significant challenge: they were compelled to push on, caught in a competitive cycle that often demanded sacrifices. This speaks to the familiar contest all endurance athletes face—balancing the drive to push limits with the need for recovery and self-care. The stakes were high; they had to ignore the signals their bodies sent, much like marathon runners who grapple with the mental voice that whispers of fatigue mid-race. In the midst of the music and cheers, the reality was stark—failure to continue meant withdrawing from the competition, a potent reminder of the athlete’s delicate relationship with endurance and the fine threshold between pushing limits and risking injury.

Many participants from that era recount stories that intertwine pain with the pursuit of success, a duality equally present in the lives of athletes today. The urgency to perform, to satisfy the expectations that often come from external validation, can lead to a mindset focused nearly exclusively on the end goal, with the journey itself—its joys and lessons—falling into shadow. This psychological strain was not unique to a past generation’s dance marathons; it resonates deeply within the endurance community, where the drive to achieve can often eclipse necessary periods of rest and introspection.

George Brown, another survivor from those marathons, encapsulated the feeling of being part of a spectacle where there was little space for anything other than relentless motion. His experience is a keen reminder of how the culture surrounding performance can sometimes mirror that of competitive endurance sports, where the pressure to keep moving can foster a mindset more aligned with circus acts than human limits. Brown’s partnership unravelled not just with the competition but through his partner’s physical exhaustion, echoing the shared journeys athletes embark on with teammates, where collective motivation can sometimes overshadow individual well-being.

Survivors of these marathons have come forward with more than just tales of dread; they share insights shaped by years of contemplation. Mary Johnson, at 88, reflected on her journey with clarity often born from time’s passage. She articulated a haunting truth familiar to those who’ve endured—an obsession with motion, almost haunting, where the drumbeat of competition reverberated far beyond the dance floor. The implication of such repetition forms a deep-rooted connection within the endurance sport community, reminding athletes that building strength, both physically and mentally, involves not just training hard, but learning to live within the moments of stillness as well.

Instead of looking solely for pride in perseverance, Johnson learned a profound lesson in self-forgiveness. Many athletes carry guilt for any perceived weakness—whether it’s needing a break or not finishing a race at the pace they hoped. It is crucial to recognize that the journey of endurance cannot be merely about relentless pushing. Instead, it must embrace a broader spectrum—acknowledging that strength is also found in the wisdom to step back, reassess, and recognize individual limits, a concept that thrives in the experiences of the marathon dancers and modern endurance athletes alike.

The collective experiences of these marathon survivors stand as a poignant reminder today: while the adrenaline of competition pushes athletes forward, it is essential to look beyond the chasing of accolades. Responsibly managing one’s physical and mental endurance is not just a matter of personal strength; it fosters a community where respect for one’s own limits, alongside the inspiration gleaned from shared experiences, leads to healthier, more sustainable practices in training and competition. The marathon dancers faced a stark reality, one that echoes through the centuries in the lives of modern athletes; the art of endurance is as much about recovery, introspection, and mutual support as it is about achieving a finish line.

As you embark on your next lengthy training session or race, consider what pacing looks like for you—not just in terms of miles or intensity, but in how you honor your body and respect your limits. In that balance lies a deeper resilience, one that is not merely marked by the endurance of movement but enriched by a profound understanding of self-care, growth, and the supportive communities that elevate the journey.